Let’s Start Here — How Does a Coal-Fired Power Plant Work?

First, we will describe a chamber called the “furnace” where the combustion takes place. This chamber could be a circular cyclone furnace or a rectangular furnace over 150 feet tall. Several large capacity fans are attached to the furnace to supply air for combustion, deliver the crushed or pulverized coal to the burners, and remove the combustion gasses.

The coal must be properly prepared for the style of furnace being used. For a cyclone furnace, the coal is crushed to the size of a kernel of corn. In the rectangular furnace, the coal is ground to a fine powder like flour.

The furnace is equipped with “burners”. Depending on the design, the number and size of the burners can vary. In a cyclone furnace there is one burner at the far end. In a rectangular shaped furnace, the burners could be at the corners or located in the walls.

The burner is where the coal fuel and air are combined, and combustion begins. As coal burns, it is oxidized at very high temperatures that can vary from 2150 °F to over 3000 °F, depending on boiler design. What remains are very hot combustion gasses and a small amount of ash.

Some of this ash, called “fly ash,” is as fine as dust and is removed in an electrostatic precipitator downstream from the furnace. Some ash is dry, and some is “sticky” and sticks to the inside of the furnace. Devices called “soot blowers” can operate continually to dislodge this ash. Some of the ash falls to the bottom of the furnace and is removed there.

To contain the high temperatures of combustion in the furnace, the walls, floor and ceiling are made of steel tubing filled with water. This part of the large chamber is called the “boiler.” In the process of keeping the walls, floor and ceiling from overheating, the internal water in the tubing becomes hot by absorbing heat from the flames. As the water rises in the walls, its temperature increases and at the same time the pressure decreases, bringing the water close to boiling. This nearly boiling water is directed to a vessel called the “steam drum”, which is the highest point in the boiler.

In the steam drum, saturated steam is now separated from the boiling water. This low energy steam is directed to sets of tubing called “superheaters.” The superheaters are located directly above the top of the flame where the very hot combustion gasses are. The superheaters absorb heat from the combustion gasses, which increases the energy in the steam.

The high energy steam, which can be up to 1000 °F and at 2000 to 2300 pounds per square inch of pressure, is then directed to the “steam turbine.” The turbine converts the energy in the steam to torque to turn the “electric generator” to produce electricity. The steam that passes through the turbine is now “condensed” back to water to complete the steam and water cycle and the water is used over again.

This is a very simplified description of the combustion process in the furnace, the ash, and the flow of water and steam in the boiler. Furnaces and boilers may vary widely in size and complexity.

Writeup and power plant diagram contributed by Tom Jasinski.

Types of Coal Ash — A Recap

There are four types of coal combustion waste (coal ash): fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and flue gas desulfurization (FGD) residue. The most concerning of these for the environment is fly ash.

Fly ash is a very fine, powdery material that is almost identical in composition to volcanic ash. Fly ash is carried up into the power plant's smokestacks with the exhaust gases from the furnace and must be captured by appropriate air pollution control equipment to meet the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Air Act standards. Fly ash makes up 70% to 80% of coal ash waste.

Bottom ash is composed of coarse, jagged particles that are too large and heavy to be carried up into the power plant's smokestacks. Instead, as its name suggests, bottom ash falls to the “bottom” of the furnace into a hopper and is removed. Bottom ash makes up around 20% to 30% of coal ash waste.

Boiler slag is bottom ash particles that have melted and fused together. It is formed only in certain types of furnaces. When boiler slag is doused with water, it turns into hard, glass-like pellets. It is a minor component of coal ash waste.

Flue gas desulfurization (FGD) residue is a by-product of the air pollution control equipment required at coal-fired power plants for reducing sulfur dioxide emissions to the air. FGD residue is initially released as a wet sludge and later dried to form a powder. Like boiler slag, FGD residue is a minor component of coal ash waste.

Handling, Storage and Disposal of Coal Ash

Power plants in Illinois can determine how to manage their coal ash, but it all must meet the applicable Illinois regulations. The options include: on-site disposal cell (dry); off-site disposal cell (dry); disposal in surface coal mines (dry); disposal in underground coal mines (wet or dry); disposal in special waste landfills (dry); and beneficial reuse.

Since fly ash and bottom ash make up the majority of coal ash waste,

Coal ash holding ponds or surface impoundments. Coal ash may be stored in wet form or dry form.

Dry disposal on-site, off-site,

The options include: on-site disposal cell (dry); off-site disposal cell (dry); disposal in surface coal mines (dry); disposal in underground coal mines (wet or dry); disposal in special waste landfills (dry); and beneficial reuse.

wet surface impoundment (coal ash pond, liquidized coal ash, storage lagoons, coal ash lagoons, wet storage)

wet disposal in abandoned underground coal mine)

dry disposal in abandoned underground coal mine — check this

wet disposal in special (permitted) waste landfills (to tamp down dust)

beneficial reuse. (has to be dry ash)

“Wet bottom ash material handling systems and surface impoundments are currently regarded as the industry standard and are the most commonly used method in the coal-fired power industry around the world. However, due to the Kingston event and resulting EPA investigation of all existing facilities using this technology, alternatives that will meet the proposed EPA regulations specifications are being considered.”

Bottom ash may be managed by combining it with water to be sluiced to a settling pond, where it may eventually be removed and disposed in a landfill or handled dry and disposed directly in a landfill.

Storage is the number one solution for coal ash disposal largely because it is generally the easiest and cheapest option. Cost is a prime consideration, and the cost is lowest when there is an available disposal site near a power plant. According to the ACAA, if the coal ash can be piped to the site, rather than trucked, and the ash is easy to handle, costs could be around $3″$5 per tonne. However, when the disposal site is further away and a more complex transport solution is needed due to either higher moisture content or larger volume, the cost could rise to $20″$40 per tonne. If a new disposal site is needed, involving an extensive permitting process, total costs will be even greater. (Best practices for managing power plant coal ash - Power Engineering International)

Storage silo technology is well-developed, but the accompanying ash handling systems involve more steps and thus are more expensive than the landfill option.

Will County has four significant coal ash storage sites.

“US activist group Southeast Coal Ash Waste says some uses of coal ash are “safer than others, and some are downright dangerous”. It cites mine-filling, where coal ash is stored in abandoned mines and quarries where it “typically is in direct contact with the water table”, as an environmentally hazardous practice, and notes that unlined landfill is potentially dangerous due to the possibility of leakage.”

How is coal ash managed in Illinois? Power plants can determine how to manage their coal ash, but it all must meet the applicable Illinois regulations. (meaning power plants can decide what method they want to use to temporarily store or end-stage (final-stage) disposal of coal ash.)

How Coal Ash Can Pollute the Environment

Coal ash can pollute the environment in five major ways: (a) leaking of contaminants into surface waters and groundwater; (b) direct contact of contaminants with soil; (c) release of contaminants into the air as dust; (d) the catastrophic/complete failure of a surface storage impoundment; and (e) wastewater discharges to surface waters from power plants with inadequate technology for pollutant control.

How it happens…

(a) The leaking of contaminants into surface waters and groundwater

(b) Direct contact of contaminants with soil

(c) Release of contaminants into the air as dust

(d) The catastrophic/complete failure of a surface storage impoundment

(e) Wastewater discharges to surface waters from power plants may pollute the environment when there is inadequate technology for pollutant control. There are longstanding federal regulations to address wastewater discharges from power plants (operating as utilities) under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). NPDES regulations arose from the federal Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972 to safeguard water quality and people's health. The NPDES program requires permits for the treatment and discharge of wastewater, whether it comes from municipal effluent, industrial effluent, mining discharges, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), public water supply treatment (sewage) plant discharges, pesticide discharges, and stormwater. Permits clearly define what and how much can be discharged, as well as monitoring and reporting requirements. While NPDES is a federal program, its actual day-to-day management is delegated to the state level, as long as states comply with the federal regulations and have the resources to do so. Illinois was granted management of its NPDES program in October 1977.

TVA Kingston Plant catastropic failure

Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities Rulemakings | US EPA

Water Permits (https://epa.illinois.gov/topics/forms/water-permits.html)

Microsoft Word - FINAL - Statement of Reasons Part 845 SOR (3-30-20).docx (illinois.gov)

Steam Electric Power Generating Effluent Guidelines | US EPA

Current Federal Coal Ash Regulations

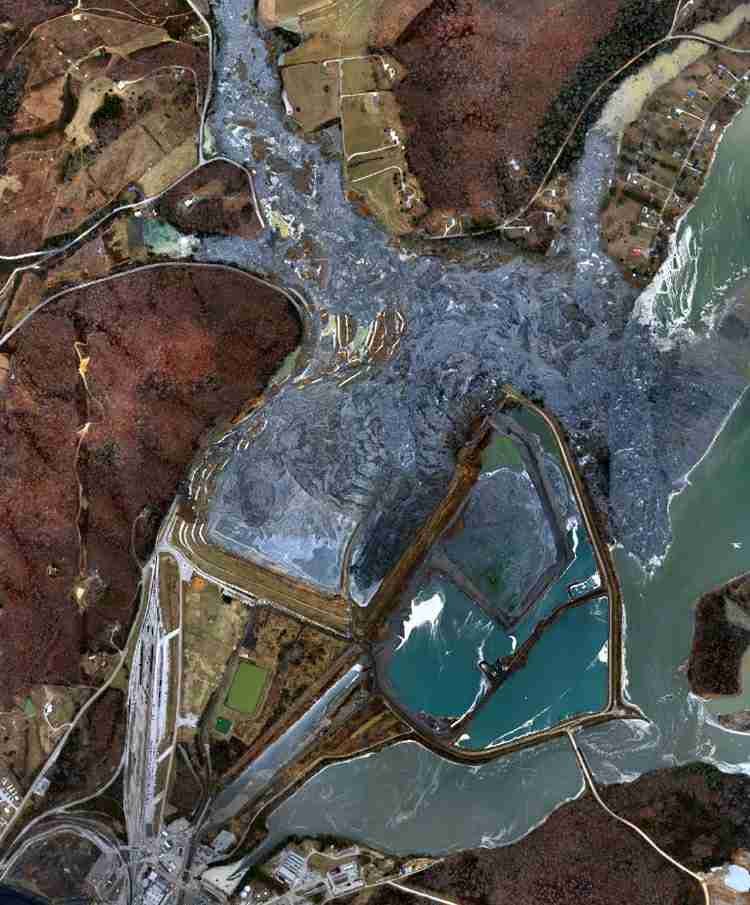

Aerial view of TVA Kingston Plant spill

The regulations provide a comprehensive set of requirements for the safe handling of CCRs in two configurations – surface impoundments for temporary storage and processing, and landfills for permanent disposal. All coal ash storage sites – active, inactive, on-site and offsite – are covered by the 2015 federal rule, as long as the facilities they are associated with are still generating power.

Originally, the 2015 federal rule did not apply to “legacy CCR surface impoundments,” meaning inactive coal ash storage at shuttered electric utilities. However, in May 2024, the U.S. EPA ordered inactive impoundments at shuttered electric utilities to comply with most of the 2015 standards already required for inactive surface impoundments at active electric utilities.

As mentioned previously, the public faces five major risks from the handling, storage and disposal of coal ash: (a) leaking of contaminants into surface waters and groundwater; (b) direct contact of contaminants with soil; (c) release of contaminants into the air as dust; and (d) the catastrophic/complete failure of a temporary or permanent surface storage impoundment; and (e) wastewater discharges to surface waters from power plants with inadequate technology for pollutant control.

These risks are addressed in detail in the 2015 final rule, as well as recordkeeping and reporting requirements. Any facility handling coal ash must have a dedicated website accessible to the public for posting certain information mandated by law, including annual groundwater monitoring data, corrective actions, and site closure plans.

The storage and disposal of coal ash was never considered for regulation in the United States until a diked containment area at Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) Kingston Fossil Plant broke open in December 2008, releasing 1.7 million cubic yards of coal ash slurry and covering 300 acres. Following this spill, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began the formal process of drafting regulations to address the treatment, storage, and disposal of coal ash.

In June 2010, an initial set of federal standards were proposed. The final rule, the Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities, was signed on December 19, 2014, and published in the Federal Register on April 17, 2015. Amendments to the 2015 final rule already have been signed into law by the EPA Administrator and additional proposed changes continue to be submitted and considered.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aerial_view_of_ash_slide_site_Dec_23_2008_TVA.gov_123002.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kingston-plant-spill-swanpond-tn2.jpg

Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities Rulemakings and Frequent Questions about the 2015 Coal Ash Disposal Rule.

Fact Sheet: Final Rule on Coal Combustion Residuals Generated by Electric Utilities (epa.gov)

Final Rule - Legacy Coal Combustion Residuals Surface Impoundments and CCR Management Units

Current Federal Coal Ash Regulations

The storage and disposal of coal ash was never considered for regulation in the United States until a diked containment area at Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) Kingston Fossil Plant broke open in December 2008, releasing 1.7 million cubic yards of coal ash slurry and covering 300 acres. Following this spill, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began the formal process of drafting regulations to address the treatment, storage, and disposal of coal ash.

In June 2010, an initial set of federal standards were proposed. The final rule, the Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities, was signed on December 19, 2014, and published in the Federal Register on April 17, 2015. Amendments to the 2015 final rule already have been signed into law by the EPA Administrator and additional proposed changes continue to be submitted and considered.

The regulations provide a comprehensive set of requirements for the safe handling of CCRs in two configurations — surface impoundments for temporary storage and processing, and landfills for permanent disposal. All coal ash storage sites — active, inactive, on-site and offsite — are covered by the 2015 federal rule, as long as the facilities they are associated with are still generating power. Originally, the 2015 federal rule did not apply to “legacy CCR surface impoundments,” meaning inactive coal ash storage at shuttered electric utilities. However, in May 2024, the U.S. EPA ordered inactive impoundments at shuttered electric utilities to comply with most of the 2015 standards already required for inactive surface impoundments at active electric utilities.

As mentioned previously, the public faces five major risks from the handling, storage and disposal of coal ash: (a) leaking of contaminants into surface waters and groundwater; (b) direct contact of contaminants with soil; (c) release of contaminants into the air as dust; and (d) the catastrophic/complete failure of a temporary or permanent surface storage impoundment; and (e) wastewater discharges to surface waters from power plants with inadequate technology for pollutant control.

These risks are addressed in detail in the 2015 final rule, as well as recordkeeping and reporting requirements. Any facility handling coal ash must have a dedicated website accessible to the public for posting certain information mandated by law, including annual groundwater monitoring data, corrective actions, and site closure plans.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aerial_view_of_ash_slide_site_Dec_23_2008_TVA.gov_123002.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kingston-plant-spill-swanpond-tn2.jpg

Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities Rulemakings and Frequent Questions about the 2015 Coal Ash Disposal Rule.

Fact Sheet: Final Rule on Coal Combustion Residuals Generated by Electric Utilities (epa.gov)

Final Rule - Legacy Coal Combustion Residuals Surface Impoundments and CCR Management Units

Major Drawback to Federal Coal Ash Regulations

Because coal ash is a waste material, the 2015 Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities final rule falls under an existing federal environmental regulation: the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). RCRA (pronounced “rick-ra”) is the nation’s primary law for the handling and disposal of solid waste and hazardous waste. Solid waste is also referred to as non-hazardous waste. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act was passed by Congress in October 1976 to deal with the ever-increasing amounts of municipal waste (household garbage/waste) and industrial waste in the United States.

Coal ash is classified and regulated only as a solid/non-hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the same regulations that govern municipal landfills receiving household garbage. Coal ash is not classified, or regulated, as a hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last ruled on this matter in May 2000.

Because coal has been labeled a solid/non-hazardous waste, putting the Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities final rule into actual practice is left up to the utilities, independent power plant owners, and state environmental agencies. Were coal ash to be declared a hazardous waste instead, potentially there would be stricter, more active, and more urgent oversight than the sort of “hands-off” impression the solid/non-hazardous label gives. The push for formally declaring coal ash a hazardous waste is now the concern of state environmental agencies and citizen lawsuits. Be assured, however, that even with the solid/non-hazardous waste label on coal ash, environmental regulations and programs developed by the states must have at the minimum the same levels of protection as federal regulations.

Read about the controversy over the classification of coal ash in Scientific American at Is Coal Ash Hazardous?

The Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities final rule should be a significant step forward, since a number of communities in the U.S. endure disproportionate levels of environmental hazards. These communities tend to be non-white, of lower socioeconomic class, and experience unequal political representation and power, giving rise to the term “environmental justice.”

Current Coal Ash Regulations for State of Illinois

“Long before the TVA ash pond failure in 2008 in Tennessee, the Illinois EPA recognized that coal combustion residue, often referred to as coal ash, might be an environmental concern. The Illinois EPA has taken a proactive approach in regulating coal ash. Since the early 1990s, new ash ponds (surface impoundments) have been required to be lined and groundwater monitoring wells have been installed at many of these new ash impoundments.

PART 845 STANDARDS FOR THE DISPOSAL OF COAL COMBUSTION RESIDUALS IN SURFACE IMPOUNDMENTS

In 1971, Illinois became one of the first states in the U.S. to develop groundwater standards, requirements for groundwater monitoring, and requirements for cleanup/remediation in the presence of groundwater contamination for coal ash surface impoundments.

According to an informational document released in September 2010 by the Office of Community Relations in Governor Pat Quinn’s administration, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (Illinois EPA) began taking a stronger approach to regulating coal ash in the early 1990s. Newly constructed coal ash surface impoundments were required to be lined and to have groundwater monitoring wells installed. However, following the massive spill at the TVA Kingston plant, an inventory published in February 2009 of 83 on-site surface impoundments at 24 power plants in Illinois indicated that only 37% were lined and only 34% had groundwater monitoring.

Another aspect of this inventory was assessing the vulnerability of groundwater near the 24 plants to contamination by coal ash, based on the sites’ geologic characteristics. A visual inspection of an aquifer recharge map for Illinois shows mostly “low” vulnerability in the majority of the state, but a definite “very high” vulnerability concentrated in the northwest part of Illinois.

The contamination potential ranges from “very high” to “low.”

The aforementioned criteria were used to develop assessment priorities for these facilities under an action-oriented strategic plan. The plan was finalized and implementation began on February 26, 2009.

along with the presence of potable wells identified near the plants, was used to determine the potential contamination threat to those wells.

The geologic vulnerability of groundwater at the 24 power plants was assessed using the Illinois’ “Potential for Aquifer Recharge” map which classifies the potential for precipitation to infiltrate the surface and reach the water table. This map can also be 1 The GMZ implemented at Havana has resulted in restoring groundwater quality to meet the Board standards. Page 2 of 10 used to determine the potential for groundwater contamination on a regional scale. Figure 1 shows the location of each power plant and the potential for aquifer recharge at each plant. This information, along with the presence of potable wells identified near the plants, was used to determine the potential contamination threat to those wells. The contamination potential ranges from “very high” to “low.” The aforementioned criteria were used to develop assessment priorities for these facilities under an action-oriented strategic plan. The plan was finalized and implementation began on February 26, 2009.

“Starting two years (i.e., 2008) ago Illinois EPA initiated an aggressive strategy to assess the geologic vulnerability of groundwater at the 24 power plants considering the presence of potable wells identified near the plants to determine the potential contamination threat to those wells. For many years, Illinois EPA has required the installation of groundwater monitoring well systems and hydrogeologic assessments at these facilities. Further, where groundwater contamination has been found we have required that cleanup/remediation be implemented.

The Illinois EPA agrees with the U.S. EPA current proposal to regulate coal combustion residue in landfills and surface impoundments. Their “Subtitle D option” proposal is very similar to what we are already doing in Illinois.”

Part 845 Standards for the Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals in Surface Impoundments

How is coal ash managed in Illinois? Power plants can determine how to manage their coal ash, but it all must meet the applicable Illinois regulations. The options include: on-site disposal cell (dry); off-site disposal cell (dry); disposal in surface coal mines (dry); disposal in underground coal mines (wet or dry); disposal in special waste landfills (dry); and beneficial reuse.

Recycling/Reuse of Coal Ash (“Beneficial Reuse”)

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency endorses the reuse of coal ash. Four main reasons for this viewpoint: (a) xxx; (b) xxxx; (c) xxxx; and (d) xxxxxx.

reduced use of virgin resources.

lower greenhouse gas emissions. (many industries, particularly cement, are energy-intensive and have very high carbon emissions. Using a pre-existing “waste” material reduces the need for manufacturing and therefore reduces the carbon emissions.

reduced cost of coal ash disposal. — link this to defining it as a hazardous waste.

improved strength and durability of materials.

Encapsulated and unencapsulated form.

How are these regulated?

EPA Decides That Coal Ash, Which Pervades Our Homes, Is Non-Hazardous (nationalgeographic.com)

Coal Ash Storage/Disposal Sites in Will County

-

Wet Storage Pond

Located at 1601 South Patterson Road in Joliet, Illinois. -

Wet Storage Pond

Located at 1800 Channahon Road in Joliet, Illinois. -

Wet Storage Pond

Located at 529 East Romeo Road in Romeoville, Illinois. -

Unlined Open Pit (former limestone quarry)

Bordered by Brandon and Patterson Roads in Joliet, Illinois.

ash-impoundment-progress-102511.pdf (illinois.gov) GMZ impact data

Citizens Against Ruining the Environment (CARE) Stance on Coal Ash Storage

Coming soon.